Back in 2015, I joined the Movember health movement, a movement that you probably have heard of having something related to men growing a moustache. As a woman, you might imagine, I did not join for the moustache thing, but rather for the cause behind the moustache symbol, that is, raising awareness of prostate and testicular cancer.

Inspired by the ladies of the Pink Ribbon movement, the Movember Foundation was founded by a bunch of Australian friends in 2003 to raise awareness of men’s physical and mental health. Over the years, the movement has grown exponentially worldwide thanks to social media. Every year, in the month of November, the Foundation organizes a campaign to raise awareness of, and donations for, cancer research. To collect donations, they use a quite upcoming crowdfunding practice in the nonprofit world called online peer-to-peer (P2P) fundraising: Individuals supporting the organization reach out to their networks via social media and request their contacts to support them with a donation.

Movember Foundation, via Wikimedia Commons.

Like many other Movember fundraisers, I put some effort into my fundraising endeavor by sharing my activities via social media, and soliciting my network of family, friends, acquaintances and beyond to support me with a donation. In addition, I teamed up with other fundraisers (my PhD advisors at the time) and we created a ‘Mo Team’, motivated to do something fun together while raising awareness and money for a good purpose. Participating in this campaign was fun, but how much money do you think I was able to raise? Unfortunately, only 30 euros! All self-donations. A bit sad. Luckily, as a team, we were able to collectively raise about 400 euros, which we considered a pretty good achievement. Yet, among the members of my team, I was definitely not the most successful fundraiser.

Now the question is: what does make a successful fundraiser? What could I have done better to raise more donations?

An answer to these questions might be useful not just for helping my ego, but also for nonprofit organizations that massively rely on online P2P fundraising. And this is where networks can help us. Now I am going to explain to you how.

Evidence from practice shows that online P2P fundraising plays an essential role in determining nonprofit organizations' fundraising success. So far, we know quite a great deal from published research about key factors explaining success in online P2P fundraisings, such as fundraisers’ characteristics and their donor networks.

On one hand, if as a fundraiser I strongly identify with the Movember cause, because I believe it is important to raise awareness of cancer prevention, early detection behavior and treatment, and I invest a lot of time and energy in the cause, I might be more likely to raise more donations. This is because playing the role of the ‘campaign champion’ causes the so-called ‘champion effect’, which can attract and motivate more people to support the cause.

On the other hand, it has been observed that if my network of donors (as those family, friends, acquaintances and beyond, who directly donate to the cause) is large, then it is likely that there will be several donations. This is an example of what scholars call, instead, the ‘network effect’: the more people you know and can reach, the more donations can be collected. Yet, donations often turn out to be small, especially if solicited via social media, like via Facebook Causes, because often donors feel satisfied to donate a small amount, especially when they know that many others might do the same.

However, research has overlooked the fundraiser networks, that is, the relationships among fundraisers (like me and my PhD team, but also other people fundraising for the cause) and how these affect fundraising outcomes.

Why should we care?, you might ask.

My answer is that investigating the connections among fundraisers is important because relationship-building is an essential asset for nonprofit organizations to support better coordination of collective fundraising efforts, and, ultimately, to collect more donations. When people are connected to each other, and with connections I mean they know or they communicate with each other, they can accumulate various types of resources that can help them achieve a certain goal.

In fundraising, as we saw above, being connected with many people (i.e., having a big network of people you know and are in touch with) can provide fundraisers with a bigger pool of potential donors (donor network), hence also larger opportunities to raise donations. In addition, fundraisers can team up, like me and my PhD team, unify forces to reach an even larger group of potential donors, and achieve a shared goal. In jargon, this set of resources is called social capital. And networks can help us accumulate such resources, as we saw above. Hence, networks can help us in understanding how fundraisers can succeed in collecting donations for social causes, like in the case of the Movember campaign.

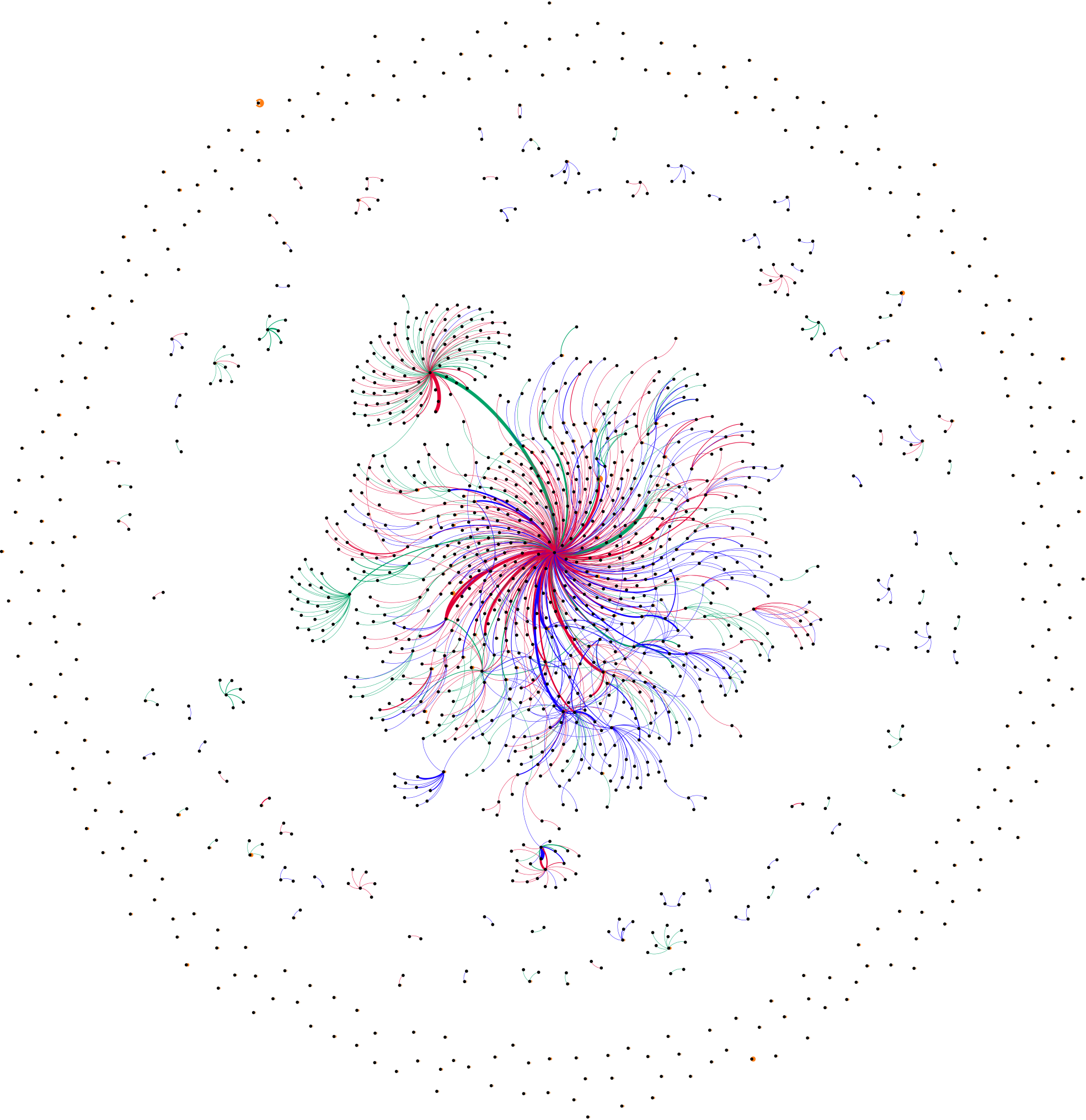

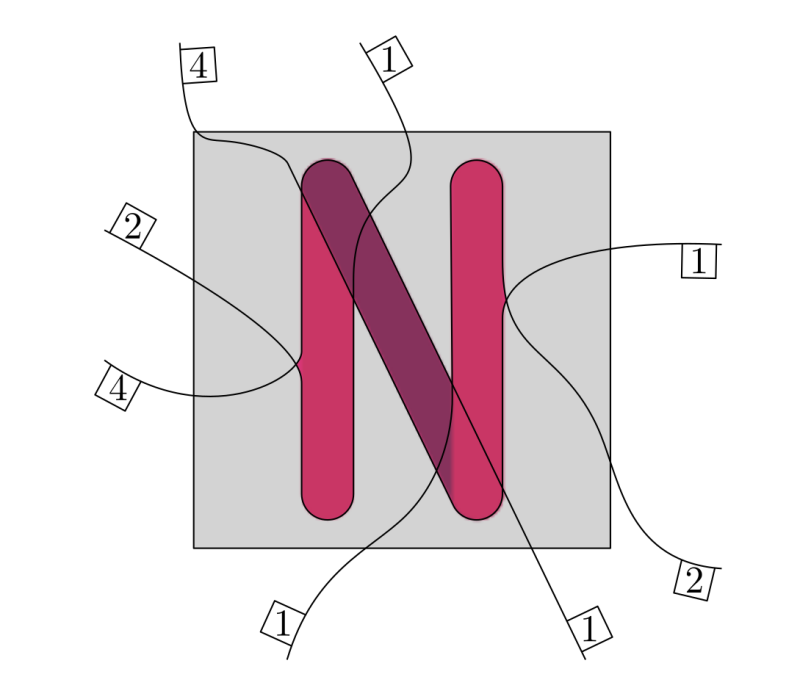

Now, if we talk in network terms, try to imagine that Movember fundraisers, like I was, are the nodes of the network and the edges that link the nodes express some sort of connection or relation between the fundraisers (like me connecting to other fundraisers). Such connections could be as simple as the relation of knowing each other or being part of the same fundraising team (like me and my PhD supervisors). If we expand our landscape of possibilities, a connection can also arise from the exchange of messages, like how fundraisers communicate with others in social media (like me mentioning or tagging my PhD supervisors or other fellow fundraisers on Twitter). While in the first case we call the emerging networks as social networks (e.g., knowing each other), in the latter case we rather refer to communication networks (e.g., exchanges messages on social media).

In a recent study, I investigated those networks effects to understand the variations in the total amount of collected donations by individual fundraisers during the during the 2014 U.S. Movember campaign.

From tweets to communication networks. The nodes in this network stand for people who have tweeted using #hashtags related to the Movember campaign. The edges are colored depending on the type of tweet: red for a simple mentioning, blue for retweets, green for answering, and orange for a common (unrelated) tweet.

On one hand I looked into the communication networks between fundraisers during the campaign, i.e., how fundraises interacted with each other on Twitter. On the other hand, although the Movember campaign predominantly took place online, in the opening example I highlighted how the Foundation also encourages collective participation and the creation of fundraising groups to build connections and strengthen camaraderie with friends, peers, colleagues, and acquaintances for the organization’s cause (like my PhD supervisors and I did).

What were the main results of this study and what do they mean?

- Fundraising success was positively associated with a fundraiser’s moderate level of centrality in Twitter communication networks, that is, the relation between central network positions and fundraising success was not linear.

- What does it mean? Being central in the communication process with other fundraisers helps me reaching out to more people and doing it faster. Yet, being too central in the communication process turned out to be counterproductive!

- Why? Because if I am at the center of a large communication network, although it might be easier to reach out to more fundraisiers and with them their donors, paying equal attention to all of them, nurturing a good and clear communication, so to also gain their trust, might be more complicated and time consuming.

- Fundraising success was positively associated to participating in a fundraiser group compared to alone. Yet, if the group (network size) was too big, that might backfire on the fundraising performance.

- What does it mean? That participating in fundraising groups is beneficial because being part of such a group (like me and my PhD team) means having stronger connections between group members, which can help coordination of activities and collective effort. In other words, the total amount of donations I raise when being a group member can be much higher than raising donations alone. Yet, if the number of such connections (members of the group) is too high, I might lose all the benefits

- Why? Because if I have too many connections, that is, too many members in my group, I might experience difficulties in cultivating resourceful relationship with all members, thus coordinating efforts and agreeing on goals can be more challenging. This can pose significant constraints to the positive benefits of having several connections.

- Fundraisers interacted only marginally on Twitter but preferred to connect with each other outside these platforms and engage in group fundraising. In other words, there was almost no overlap between the Twitter communication network and fundraising group networks.

- What does it mean? That fundraisers marginally used social media for communication and coordination among fundraisers, and they rather used them for connecting with potential donors.

- Why? Because fundraisers are embedded in multiple networks, online and offline, and not all such networks equally bring the expected advantages.

So, what are the key take-aways? As fundraisers, we can learn to

- MO TOGETHER AND NOT ALONE!

- Team-up with other fundraisers: look in your workplace, at school or group of friends, NURTURE YOUR NETWORKS!

- INVEST TIME in improving your COMMUNICATION SKILLS on social media.

What can you learn as a nonprofit? That you should:

- EDUCATE your fundraisers on how to harness their connections with other fundraisers and not just merely with their donors.

- RECRUIT fundraisers who are open to developing relationships with other fundraisers, particularly in groups, and find ROLE-MODELS who can inspire other fundraisers to take successful action.

- And last but not least, encourage and support GROUP PARTICIPATION and a SENSE OF COMMUNITY among your fundraisers (e.g., promoting P2P fundraising in the workplace or educational and social settings)!

The research described in this article is based on

Priante, A., Ehrenhard, M. L., van den Broek, T., Need, A., & Hiemstra, D. (2022). “Mo” Together or Alone? Investigating the Role of Fundraisers’ Networks in Online Peer-to-Peer Fundraising. Nonprofit and voluntary sector quarterly, 51(5), 986-1009.